Network Motifs and Dynamic Consistency

Many complicated networks can be studied as smaller components. Some of these smaller network components are common enough that they have categorized and labeled

as "motifs." Studying these network motifs in isolation can give a detailed understanding of smaller systems with somewhere between 2 and usually 5 or so

interacting variables. However, these small systems rarely exist on their own. They are frequently smaller subsystems of much larger systems.

This is true in economics, traffic, medicine, cell networks, and this is certainly the case in ecology.

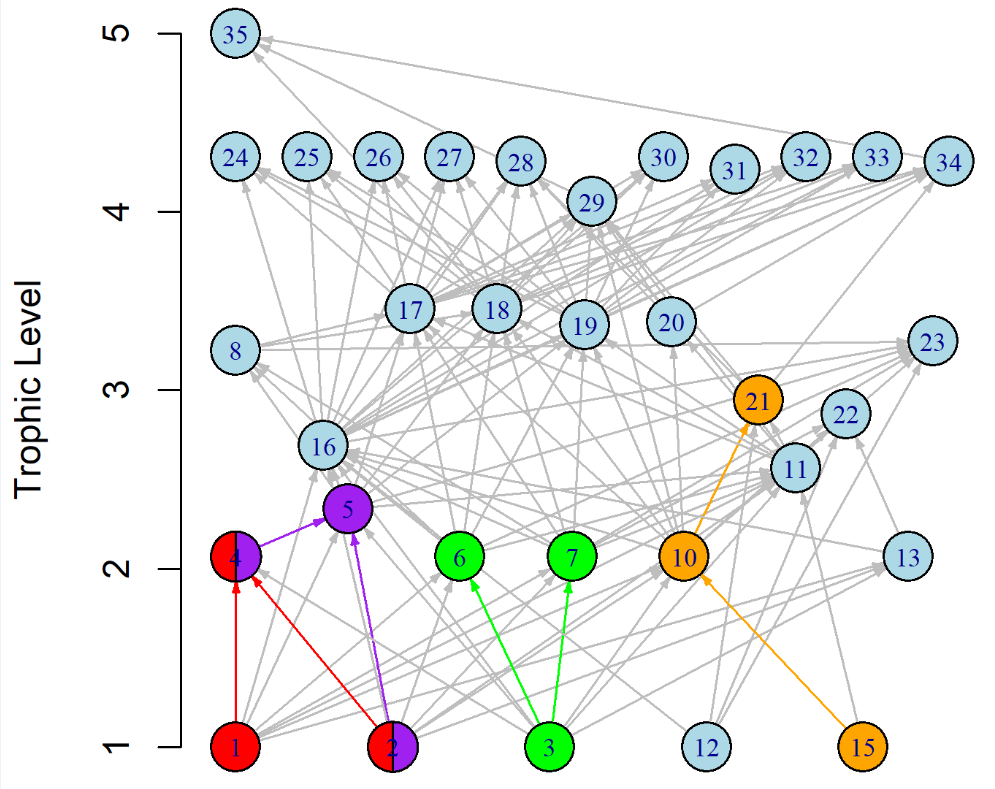

For example, a 3-trophic level food chain is relatively well understood in its behavior, but in nature a 3-trophic level food chain (e.g., the orange colored motif shown in Fig 1 below)

is connected to numerous other

species through competition, consumption, parasitism, or mutualism. The question then becomes, how much are the dynamics of a 3-trophic level chain perserved in different

degrees of larger communities?

Specifically, we can ask: How does the utility in studying smaller subsystems scale to the necessary work on larger networks?

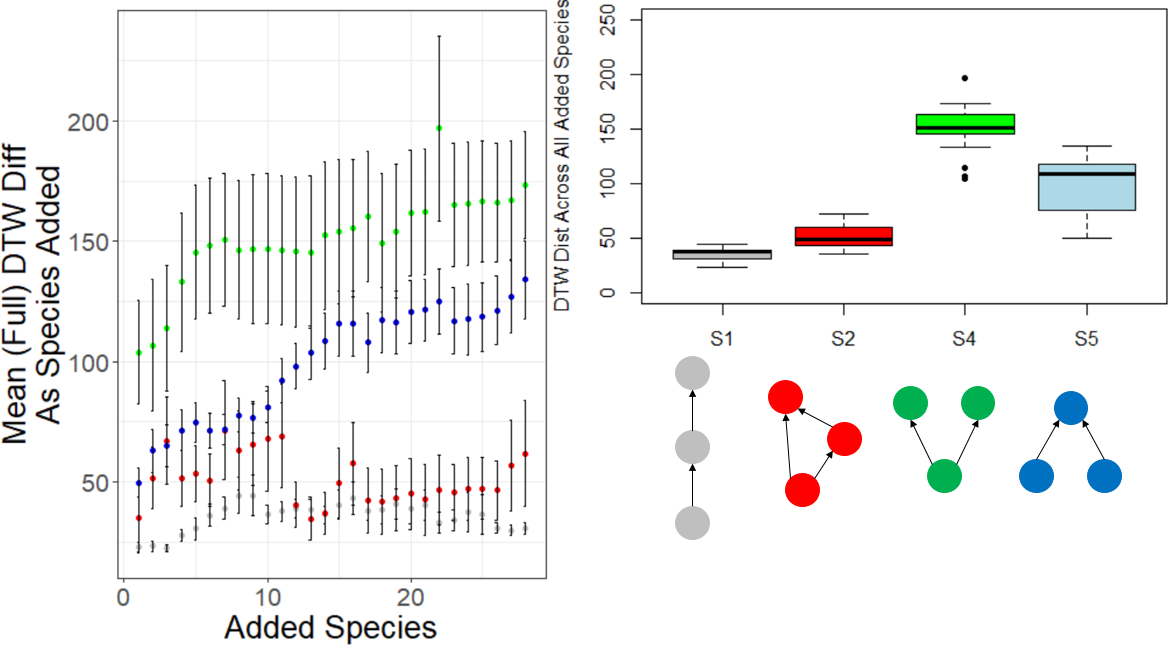

Using a series of network modeling tools, we have begun to address this question in real-world networks such as the Lake MI food web network shown on the left. By starting with motifs and using network assembly, we can gauge how much key characteristics of our original network change depending on the inclusion of different aspects of our broader network. An example of such work is presented below using a different network, a food web from the Chesapeake Bay.

This research is still being conducted. Stay tuned for more results!